- Home

- All About Mangroves

All About Mangroves

A mangrove is a tree or shrub that grows mainly in tropical coastal and swamp areas. A mangrove ecosystem is the entire environment that surrounds the mangrove trees. This includes other plants, animals, soil and microorganisms. They all depend on each other for survival.

While most plants have roots that are entirely underground, mangroves have a lot of tangled roots that grow above ground, called aerial roots. Aerial roots serve as “snorkels” for breathing when the soil is flooded or has little oxygen.

Jamaica is home to four species of mangroves:

Red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle)

Black mangrove (Avicennia germinans)

White mangrove (Laguncularia racemose)

Button or Buttonwood mangrove (Conocarpus erectus)

These mangroves are typified by a low diversity of species with black mangrove dominating. The red mangrove is the second-most dominant species found in Jamaica.

Rhizophora mangle dominates the coastline as it is the most resistant to water movement generated by tides and occasional waves and has viviparous seedlings that are adapted to the lower intertidal areas and associated water movement. Rhizophora roots are also believed to play a successional role in trapping both Rhizophora species and other smaller seedlings of the other species. Mangrove forests normally show zonation with Avicennia germinans and Laguncularia racemose occurring further back from the deeper tidal zone as their propagules are smaller, less resistant to water movement and physical injuries, and are often washed further inland.

Jamaican records and literature suggest a fourth species of mangrove tree; the buttonwood or button mangrove, Conocarpus erectus. However, this species should be classified as a mangrove associate and not a true mangrove species, as it does not possess viviparous seedlings, the wind dispersed seeds cannot germinate in salty water and it lacks special root adaptations to deal with prolonged inundation.

Mangroves are one of only a few tropical plants that have adapted to survive in salty water along the shores, estuaries and coastal areas of tropical countries like Jamaica. Salt normally kills plants, but mangroves have created an elaborate root system that can filter out as much as 90% of the salt in the seawater. Meanwhile the leaves store freshwater and excrete excess salt. The mangrove breathes by growing many long thin roots that stick up out of the sea water like snorkels. These roots also help stabilise the mangrove tree. Furthermore, some species of mangrove have developed a unique way to reproduce itself by producing seed pods that germinate on the tree. When these seed pods fall, they are ready to take root immediately.

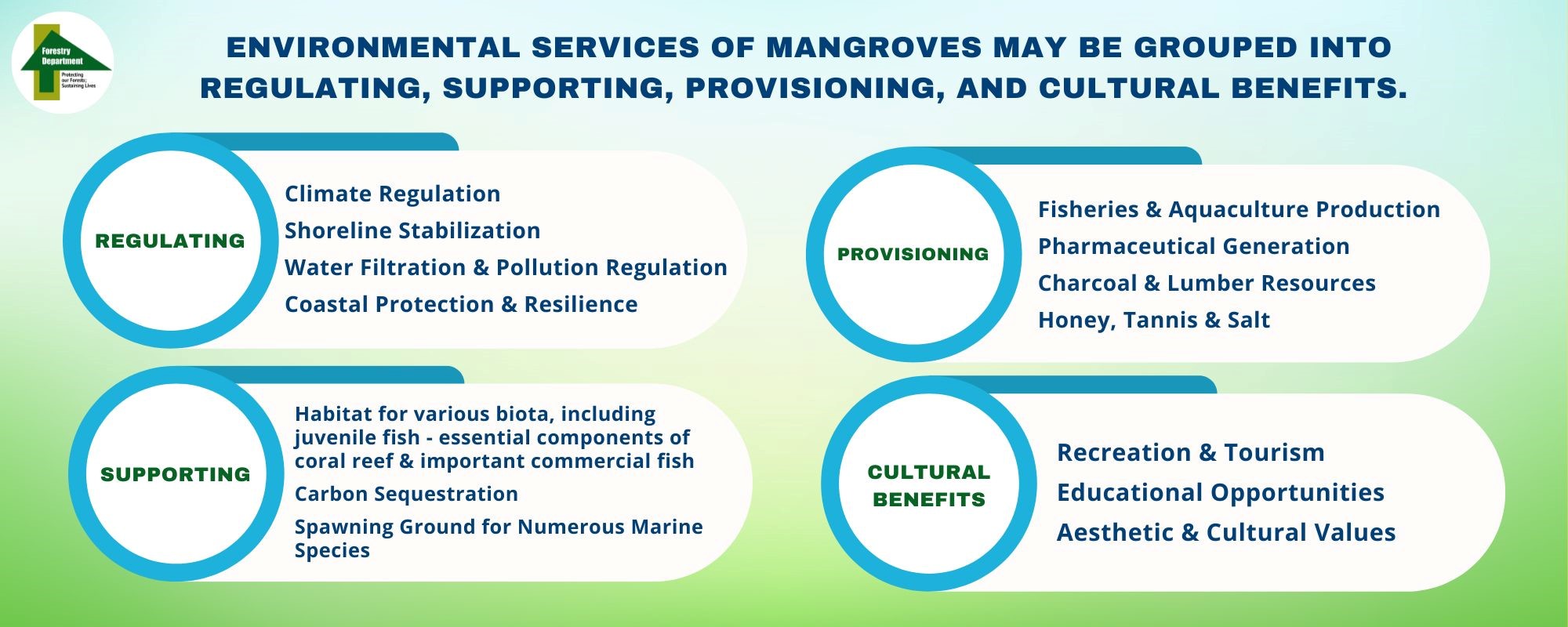

Mangrove ecosystems are considered globally significant ecosystems because they provide multiple ecosystem services, including supporting the resource base of several economic and subsistence livelihood activities.

- Mangrove forests and swamps are considered the most cost-effective method of shoreline defence. They are part of nature-based solutions for protecting shorelines from storms and floodplains from absorbing excess water runoff. They help reduce coastal flooding by acting as physical obstacles to the flow of water and waves. The dense roots and stems of a mangrove forest provide a drag resistance that is strongly related to wave reduction.

- Because of their submerged root system, mangroves retard water movement and trap suspended materials and the remains of organisms associated with the mangroves. The accumulation of this organic material contributes to raise the soil level. Continued accumulation of soil, particularly by sea fringing mangrove stands, builds the shoreline seaward. In the course of this process, the rich protected substrata provide a habitat for a large variety of organisms that serve as food for marine fauna, including oysters and crabs, which are a harvestable source of protein.

- Mangroves provide an array of benefits to coastal communities, including wood and non-wood forest products and environmental services encompassing shoreline protection, erosion control, water filtration, nutrient cycling and biodiversity conservation, recreational and educational opportunities in addition to their role as nursery habitats for a variety of fish species.

- Mangroves are also recognized as valuable to climate change mitigation efforts due to the outsized amounts of carbon contained in above and below ground mangrove biomass and trapped within the soils between mangrove root systems.

The value of Jamaica’s mangrove forests for flood risk reduction to the nation’s built capital is estimated at more than J$336,000 per hectare per annum. The loss of Jamaica’s mangroves would further result in a 10% increase in the total number of people flooded every year.

One of the most notable benefits of mangroves is the protection offered during high intensity storms. During these storms, mangrove forests protect approximately 770,000 people that live in coastal areas and saves the country nearly J$ 322 billion in damages. This translates to economic benefits of more than J$25 billion per hectare of mangroves. For instance, analysis of recently lost mangroves in Old Harbour Bay show that the loss of these mangroves has resulted in the loss of flood protection benefits of more than J$136 million each year.

The mangroves and sand dunes of the Palisadoes and Port Royal Protected Area are well documented to provide natural coastal protective services associated with the relatively calm waters of the Kingston Harbour. This vegetation flanking the southern harbour boundaries, and which keeps the tombolo intact from erosion, makes for calm weather conditions allowing regular ship docking and transhipment activities, which are essential to the Jamaican economy.

Jamaican mangroves ecosystems provide habitat for many threatened species, including the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List and the West Indian Whistling Duck (Dendrocygna arborea) and the American Crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) that are listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and listed in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). The majority of American crocodile populations in Jamaica inhabit the mangrove swamps and marshes along the southern coast of the island, including the Black River Great Morass in St Elizabeth parish and Milk River in Manchester parish, with a few isolated populations on the north coast in the parishes of Hanover and Trelawny.

Mangrove habitats further support a large group of animals belonging to a range of taxonomic groups. Many of these animals live in association with the prop roots of the red mangrove or may be found on the benthos of the mangrove lagoon. Yet others live in the mangrove forest, occupying forest floor or canopy.

Common mangrove species identified by studies conducted by the University of West Indies include a) Cnidaria (anemone and jellyfish), b) Annelida (ringed worms); c) Crustaceans (including such animals as lobster, crab, shrimp, oysters, barnacles, clams, conch, snails, urchins, sand dollars, sea stars and brittle stars, and sea cucumbers), and; d) and many types of vertebrata.

Jamaica has a high level of endemism for many species of animals. One of the most important endemic species to Jamaica is the Jamaican iguana (Cyclura collei)). The Jamaican iguana is known to live in low-lying dryland ecosystems and marshlands that are adjacent to and highly connected to mangrove ecosystem health. The Jamaican Iguana was once widely distributed across Jamaica, but now only a small population survives in the Hellshire Hills, located on the south-central part of the Jamaica and within the Portland Bight Protected Area. The Jamaican iguana is currently listed as critically endangered.

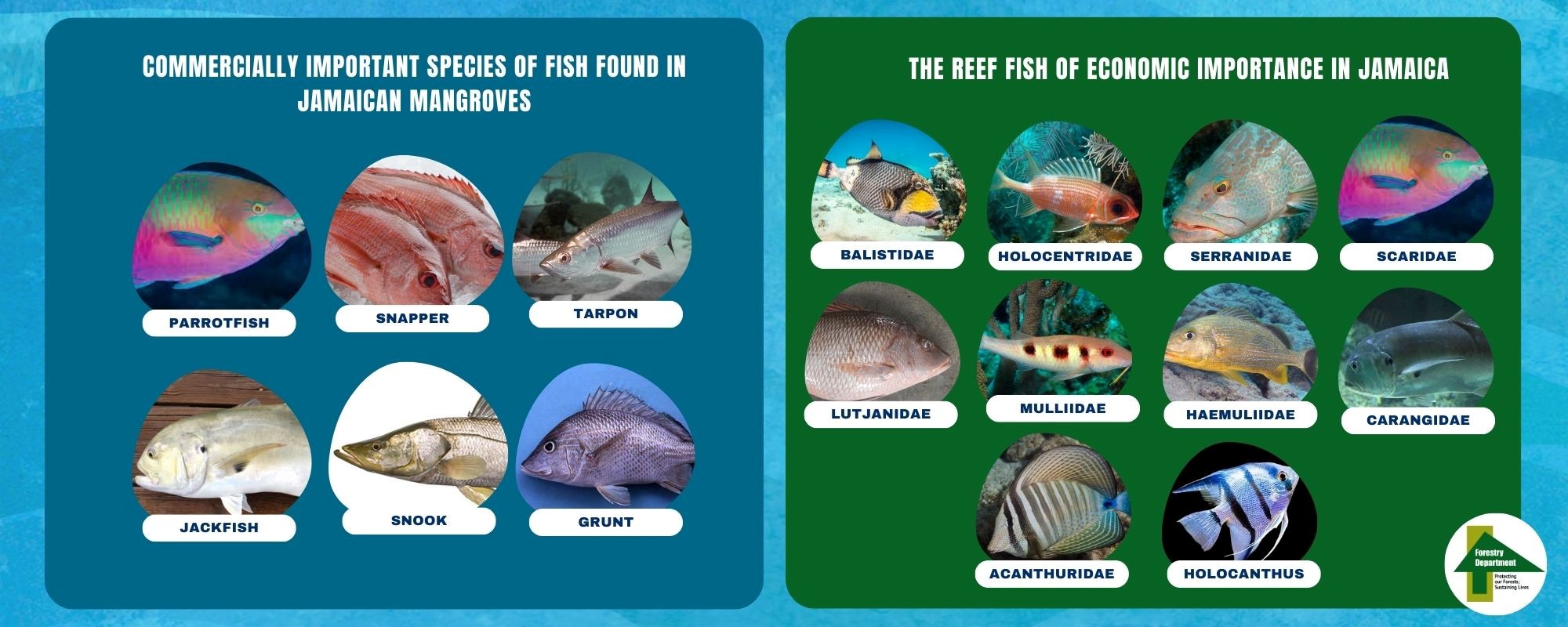

Mangroves provide home and shelter for many fish species and the sustainability of Jamaica's artisanal, recreational, and commercial fisheries are directly dependent upon mangrove ecosystems. These include fish species that spend part of their lifecycle in wetlands during breeding and spawning. Mangroves also serve as a nursery for juvenile fish.

Jamaican mangrove habitats are known to host a vibrant community of other flora and fauna, including several additional halophytic plant species.

In general, there is very limited data on the spatial extents of mangroves since mangroves in Jamaica are typically classified and counted together with fresh-water ‘swamp’ forests and only recently have mangrove extents been recorded separately. Though data on individual wetlands exist, there is little documentation of long-term trends in the extent, status and health of Jamaica’s mangroves.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) indicates that in the 1970’s, mangroves might have extended across more than 15,000 hectares in Jamaica. Estimates of mangrove extents since then vary a lot but it appears that the main coastal wetland areas of the country where mangroves are found amounted to approximately 11,674 hectares in 2010. This increased to 16,735 hectares and then declined to about 9,800 hectares in 2013 due to human activity.

It was thus assumed until recently that coastal mangroves in Jamaica covered an area of around 9,800 hectares as per the penultimate estimate from 2013, making up less than 3% of Jamaica’s total forest cover while 82% of the mangrove habitats were found on the country’s southern coastline. This area under mangroves represents a linear coverage of 291 km or 30% of the 955 km of the coastline of Jamaica.

Between 2019 and 2021, the Forestry Department conducted detailed assessments of Jamaica’s mangrove habitats with support from the European Union Budget Support Programme (EU-BSP) to underpin the National Mangrove Management Plan[RR1] . The assessment reports revealed that there are 96 mangrove habitats in Jamaica today covering an area of 13,784 hectares. The most significant percentages of coastal mangroves are found in the southern sections of St. Thomas, St. Catherine, Clarendon, St. Elizabeth and Westmoreland parishes, primarily in sheltered bays, estuaries, and inlets. Wetland parcels were identified as mangroves and swamp forests by the spatial mapping software if these areas had over 1 hectare mangrove forest species.

Although most mangrove forests across the island are showing a decrease in area, most of the decline is seen for areas where coastal developments have taken place particularly along the north coast. For instance, according to NEPA, Jamaica’s northern parishes (main tourism belt) have seen a decline in nearly 300 hectares of mangroves between 2005 and 2010. These changes are however relatively recent and are built on a long history of mangrove loss and degradation.

According to the Forestry Department’s land use cover assessment of 2015[RR2] , wetlands, comprising mangrove forest and swamp, experienced a loss of approximately 95% or 2,123 hectares between 1998 and 2013. However, this relates mainly to a loss of swamp forest, largely due to agricultural activity and infrastructure development including buildings and roadways.

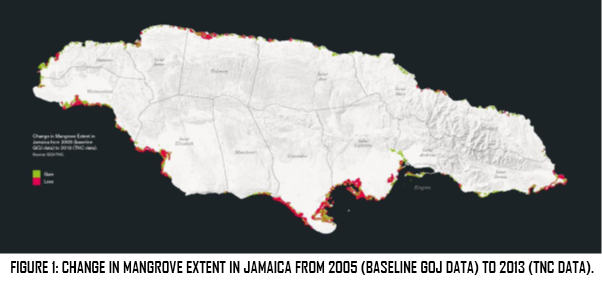

Mangrove losses and gains across Jamaica are not spatially uniform, with some areas seeing significant losses and other coastlines witnessing gains (Figure 1). For example, Jamaica’s southern coastline has seen some increases in mangrove cover in recent years, for example in the protected region of the Negril Great Morass. Mangrove extents however declined in two southern coastal parishes – St. Catherine and Clarendon – by over 40%.

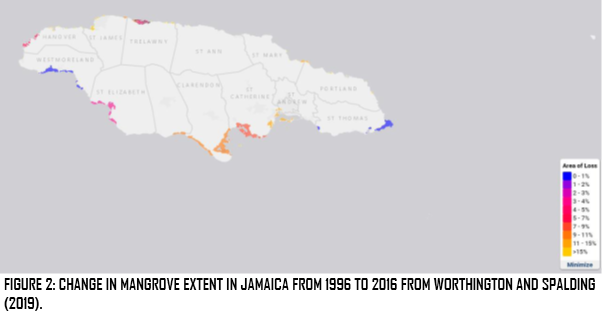

In 2019, Worthington and Spalding assessed the global change in mangrove distribution with satellite derived data from surveys in 1996 and 2016 and used these to assess the potential for mangrove restoration in areas of loss. This report estimates that more than 770 hectares of mangroves were lost in Jamaica over the past two decades. While these analyses are conducted at a global scale, they nonetheless are very useful for showing the broad patterns of change across Jamaica (Figure 2). Not surprisingly, mangrove losses are highest in the southern parishes of St. Elizabeth, Clarendon and St. Catherine and in the parish of Trelawny in the north. Mangrove losses are lowest in the St. Thomas Morass in the east and in the mangrove forests of Westmoreland in the west.

The Situational Analysis that was carried out as part of the development of the National Mangrove Management Plan presents verified accounts of mangrove losses and gains between 2017 and 2021. Over the past five years, 19.6 hectares of mangrove appear to have been lost while 2.7 hectares have been regained through restoration initiatives, resulting in a net loss of 16.9 hectares. These figures do not capture all recent changes in mangrove forests in Jamaica, but only include losses that were documented or permitted (wetland modification permits granted by NEPA). There were likely more losses from unplanned/unpermitted developments, or via developments which were not granted NEPA permits.

Jamaica has 40 Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs). The mean percent coverage of all KBAs by Protected Areas (PAs) or Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures (OECMs) in Jamaica is 22.1%. At least 13 of KBAs include areas of coastline all around Jamaica that include wetland mangrove ecosystems or are directly adjacent and ecologically connected to wetland areas. The largest KBAs that include areas in the coastal zone are the Black River Great Morass, Portland Bight Protected Area and Negril.

NEPA, in an effort to protect the country’s wetlands, has declared four Ramsar sites. These are the Black River Lower Morass in 1997, Palisadoes–Port Royal Protected Area 2005, the Portland Bight Wetlands and Cays, 2006 and Mason River Protected Area, 2011.

Jamaica’s mangrove ecosystems are currently experiencing several direct and indirect threats. Collectively, these threats have resulted in a significant decline in the area of mangrove and associated wetland ecosystem, resulting in a major decline in ecosystem services that have had significant impact on both local communities and a national economy that relies heavily on nature-based tourism.

Coastal ecosystems including mangrove forests continue to be lost and degraded. Globally, mangrove forests have seen area losses of about 35% since original global recordings in the early 1980s. Their annual loss rate is about 2.1% from natural forces such as hurricanes and associated winds, as well as coastal development and aquaculture. The loss of mangroves and coral reefs will result in the loss of their ecosystem services. The loss of mangroves will also result in an increase in flood damages to communities that are otherwise protected by these ecosystems.

Jamaica – like much of the Caribbean region – is at high risk from coastal hazards due to its exposure to tropical storms, high levels of coastal development, and vulnerable coastal communities. Mangrove forests in Jamaica suffer two distinct environmental problems, namely habitat loss and/or a decline in biodiversity and poor health of mangrove ecosystems.

The net loss over the last five years of only 16.9 hectares or 0.1% of the 13,784 hectares of mangrove areas, as assessed by the recent Forestry Department reports, conceals the fact that the health status of many mangrove areas has been deteriorating. The Forestry Department’s EU-BSP Year 3 Mangrove and Swamp Forest Verification Report reports on 35 mangrove habitats covering in all 7,614 hectares. Of the 35 sites, nine had a fair health status and two a poor health status. Anthropogenic disturbance was observed on 74% of the sites and invasive species were found on 51% of the sites. Overall, 845 hectares or 11% of the assessed area suffered anthropogenic disturbance.

Evidence thus strongly suggests there is an overall declining trend in Jamaica’s mangroves. Losses and gains across the island are not spatially uniform and the main drivers of loss vary. Northern parish mangrove loss is more often associated with tourism and residential development, while port and industrial development have been a main driver in southern parishes. Of the seven south coast parishes, five showed an increase in wetland coverage between 2005 and 2011 suggesting renewed possibility for successful mangrove restoration. In a recent global assessment, an estimated 770 hectares of mangroves have been lost in Jamaica between 1996 and 2016, more than 70% of these mangroves could be potentially restorable. Between 2017 and 2021 another 19.6 ha was lost while 2.7 ha were regained through restoration initiatives.

The reasons for this loss and degradation of Jamaica’s mangrove forests are multiple.

Approximately 70% of Jamaica’s population lives in coastal areas, and over 50% of its economic assets such as airports, harbours and tourism infrastructure are located on the coast. Between 1988 and 2011, 11 major storms made landfall in Jamaica, causing significant damages to people and property. Such natural disasters remain a main risk to the country’s economy and economic outlook with significant challenges for disaster recovery and re-development.

Direct threats to mangrove ecosystems in Jamaica resulting in habitat loss stem mainly from the direct clearing and reclamation of mangrove habitat for coastal development through cutting mangrove trees and dredging and filling the wetland areas to construct buildings, roads, and other types of infrastructure.

Coastal development has been the main driver of mangrove loss across Jamaica. In the north of the country clearing and reclamation of mangrove habitat has been particularly driven by residential and tourism development, especially where hotels and restaurants seek land as close to the coastline as possible driven by tourist preferences, whereas in the south, port and industrial development has contributed substantially to losses.

With the growth of Kingston on the south coast, and Montego Bay, Ocho Rios and Port Antonio on the north, much of Jamaica's original mangroves and coastal wetlands have been destroyed by coastal development and rapidly urbanizing tourist areas are threatening many of the remaining areas.

The greatest destruction has occurred in the larger estuaries now used for harbor facilities such as along Hunt's Bay and the Kingston waterfront as a result of an expansion of marine terminals and warehouses, freeport sites for industry, and residential subdivisions (particularly in estuarine locations - harbour facilities such as along Hunt's Bay and the Kingston waterfront)

In Port Royal and Palisadoes, on the south coast of Jamaica mangroves were destroyed to facilitate road, airport and marina construction.

Shoreline hardening using artificial structures and developing coastlines with hard barriers has prevented landward mangrove migration, resulting in a process commonly known as ‘coastal squeeze’.

As highlighted by the Forestry Department’s EU-BSP Mangrove reports (2019-2021) , most of the mangrove losses were related to tourism development. This data further validates the opinions reflected from the stakeholder engagement surveys, where tourism related developments were regarded by respondents, as the most detrimental industry to forested wetland conservation in Jamaica. The 2010 NEPA State of the Environment Report stated that tourism expansion alone in Trelawny parish was responsible for over 160 hectares of mangrove forest reclaimed between 2005 and 2010.

The NMMP team’s review of recent mangrove losses revealed at least one case where mangrove losses were facilitated and/or implemented by GOJ Agencies: The Port Authority and Trelawny Municipal Corporation. The relocation of the Falmouth Market involved the reclamation of 6 ha of mangrove forest, and perhaps unwittingly facilitated further expansion of an adjacent informal settlement. The reclaimed market area was thereafter used as an access road for the adjacent community.

Overwhelming evidence points to the notion that tourism-related pressure in the last decade has been the main motivation for mangrove forest loss in Jamaica. Jamaica’s northern parishes (main tourism belt) have seen a decline in nearly 300 hectares of mangroves between 2005 and 2010. However, it must be stated that tourism related developments receive a natural “bias” as they are often publicly documented and circulated in the mainstream media. The FD EU-BSP report and the NMMP consultant team unearthed a few cases where mangrove lands were degraded unwittingly through aquaculture or agricultural expansion, especially in Southern Clarendon. The expansion of fish farms in Old Harbour Bay, Milk River and Mitchell Town have removed mangrove ponds.

In addition to loss of mangrove areas due to documented and permitted tourism and infrastructure developments, there have been undetected losses due to small-scale developments, such as single house lots, where no NEPA Development Plan/Order is required, in which case permits are issued by the local authorities. NEPA Development Orders are neither required for:

- Works carried out by a Road Authority for the purpose of maintenance or improvement on land within the road boundaries,

- The carrying out by any local authority or statutory body of works for the inspection, repairing or renewing of sewers, mains, pipes, cables or other apparatus or the breaking open of any street for that purpose.

- The use of any land for the purpose of agriculture or forestry and the use of any building occupied with the land and used for this purpose.

There is currently no requirement for wetland modification permits, and thus no reports submitted, when small-scale (e.g. single houses) development is permitted by municipal corporations.

Mangrove forests have played an important historical and traditional role in many Jamaican coastal communities with services such as wood supplies for construction, daily-use and artisanal products, small-scale farming, firewood (charcoal) and subsistence fishing in canals and rivers. As a result, these forests are threatened in some areas due to over-exploitation of resources.

Common human activities of mangrove forests in the region include grazing of cattle and other livestock, subsistence agriculture, charcoal production and construction from mangrove wood and timber, and subsistence fishing in the canals and rivers.

Extractive industries (removal of fish, shellfish, reptile skins, and honey at subsistence and artisanal levels) are less damaging, as they require the mangrove tree to replenish to give more of its product over time, while the trees continue to sequester carbon, produce oxygen and support biodiversity in most cases. Most extractive industries are more damaging to trees than to the hydrology of the forest.

Mangroves are also increasingly facing threats from marine litter, especially in lagoon and riverine areas where trash is directly dumped or is flushed into coastal waters through storm drains. Mangrove prop roots and soils can be covered in plastic and other litter, preventing uptake of important gasses and nutrients. Mangrove roots also trap and collect litter into localized areas, having a major impact on the mangrove ecosystem biodiversity.

Another indirect human impact is pollution from human activity, such as outfalls from waste-water treatment plant or waste from construction activities that can cause already stressed mangrove habitats to either degrade or be completely lost, and negatively impact their ability to recover after natural stressors such as a hurricane or drought.

The city of Kingston discharging its waste into an enclosed harbour has many consequences to the organisms inhabiting the area, including humans. Pesticide contamination (e.g., diazinon and aldrin) has also been found in oysters and fish within the Kingston Harbour and its mangroves.

The most pronounced indirect threat to biodiversity and health of mangrove ecosystems in Jamaica is the numerous ways in which the hydrological conditions have been altered. Among the many ways this can occur include the alteration of river flows for irrigation for large-scale sugarcane and banana agriculture and more localized aquaculture, to impacts on surface and water table levels and salinity due to road and housing construction, unsustainable pumping, and illegal settlements and unchecked urban sprawl.

In many case studies of mangrove land-use changes, features to connect and maintain mangrove hydrology (e.g., culverts) are often omitted due to cost, lack of proper planning and monitoring or ignorance.

The most recent diagnosis by the University of the West Indies, Centre for Marine Sciences team for The Nature Conservancy revealed that 13.3 hectares of mangrove forests in Old Harbour Bay experienced die-back resulting from hypersalinity conditions which were created by anthropogenic actions. In this case study, shrimp farm operations in the 1980’s redirected riverine waters from a small tributary which historically entered a mangrove area into their operations and then out into the area’s main inlet canal. The operators diverted their effluent water into a solitary culvert, which lead into and sustained the mangrove area up to 2007. This culvert was unwittingly blocked by residents due to construction failure, preventing fresh water from entering the mangroves. This mangrove forest was converted to a salina over three decades

While less impactful, mangroves ecosystems are also subject to water quality issues. Mangroves tend to trap and concentrate pollutants. The extent to which various types of pollutants, other than oil and sediments, contribute to mangrove destruction is uncertain. However, it is known that in mangrove-fringed estuaries, the concentration of pollutants, and/or temperature and salinity changes, tends to upset the delicate balance of microscopic life, drastically altering the entire coastal ecosystem.

Significant mangrove degradation may also be attributed to sugar cane farming.

Mangroves are further indirectly threatened by the introduction of several invasive species, including several plant species like hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) and cattail (Typha domingensis) and numerous land and marine animals, including feral goats, green mussels, ship worms, and lionfish.

In general, adverse impacts to mangroves from climate change include increases in sea-level, frequency and/or intensity of storms and associated storm surges, temperature and aridity. This is leading to increasing wave energy uprooting mangrove trees, accelerating shoreline erosion, and making natural repopulation and replanting efforts more unsuccessful.

Jamaica’s forests have been experiencing higher temperatures and decreased rainfall and this trend will continue. Sea levels are projected to rise from a mean of 0.24 to 0.30 metres, according to the various RCP models, resulting in raising water salinity in mangroves and other coastal forested wetlands, which may result in dieback of the mangroves.

While mangroves in the Caribbean appear to be keeping pace with current sea-level rise rates of 1 to 2.5 mm/year this may not remain the case with accelerated sea-level rise in the future. Increases in the frequency of droughts and reduced rainfall, related to extreme El Nino events in the Caribbean, can further impact mangroves by limiting sediment supplies.